The circumstances of the likely-mixed-faith wedding suggest that it violated a Vatican decree called Ne Temere, which took effect in 1908, requiring Catholics to have their marriage witnessed by a priest who was the pastor of the Catholic or the pastor’s delegate and by two other people and registered in the parish where the marriage took place, said David Long, a canon-law expert and dean of the School of Professional Studies at The Catholic University of America.

“Based on the cursory review of the marriage license, I do not believe those requirements were met in this case, so the sacramental validity of the Riggitano-Hughes marriage is already questionable, even while its civil-law status is not questioned,” said Long, author of Newman, Canon Law, and Development: Quarrying Granite Rocks With Razors (May 2025).

Less than three years later, in March 1917, Daisy Hughes Riggitano had her husband arrested on suspicion of adultery, at a time when it was not only illegal but also civilly punishable. Also arrested shortly afterward was a 23-year-old woman, who had shortly before left Chicago for Quincy, Illinois, about 220 miles southwest of Chicago.

Giovanni’s brother-in-law told The Quincy Daily Herald that it was all a misunderstanding and that Giovanni and the young woman would quickly be proven innocent.

About two years before the arrests, the second woman, Suzanne Fontaine, had emigrated from her home in Normandy in France to New York City, where she found lodging with the Jeanne D’Arc Home “for friendless French girls,” according to the New York state census of 1915. She later moved to Chicago.

(Story continues below)

What happened in the legal case against Giovanni and Suzanne isn’t clear. But in July 1917, about four months after the arrests, Suzanne gave birth to a boy in a home for unwed mothers in Lackawanna, New York, just south of Buffalo.

Suzanne gave birth again in July 1920, to a boy named Louis, who would later become Pope Leo’s father.

Giovanni and Suzanne lived together for the rest of Giovanni’s life — about 40 years. Both took the last name Prevost — Suzanne’s mother’s maiden name — and gave that name to their two sons. Giovanni began calling himself John, the English form of the name.

A Private Marriage?

Genealogists have found no evidence that Giovanni and Daisy divorced.

Likewise, genealogists so far have found no public record that Giovanni and Suzanne ever married.

But might they have married privately in the Catholic Church?

It’s possible, Long told the Register, under certain provisions of the 1917 Code of Canon Law.

“I believe the evidence shows there would have been no prior canonical or sacramental bond between Riggitano and Hughes, which would have allowed for the canonical marriage of Riggitano and Fontaine,” Long said.

“If they pursued such a marriage in the Church, it would have been a ‘marriage of conscience’ according to the norms” of canon law, Long said — “a fully valid sacrament in the eyes of the Church, yet kept secret and not registered with civil authorities.”

No records have surfaced that would establish such an arrangement, however.

“As always, the Church’s priority [is] to uphold the sanctity and indissolubility of marriage, but also to pastorally care for souls in irregular situations. If a Catholic couple (Riggitano and Fontaine) truly had no impediment in God’s eyes, the Church could validate their union sacramentally, even if civil society could not recognize it, provided that the sacramental marriage did not produce public scandal or legal conflict,” Long explained.

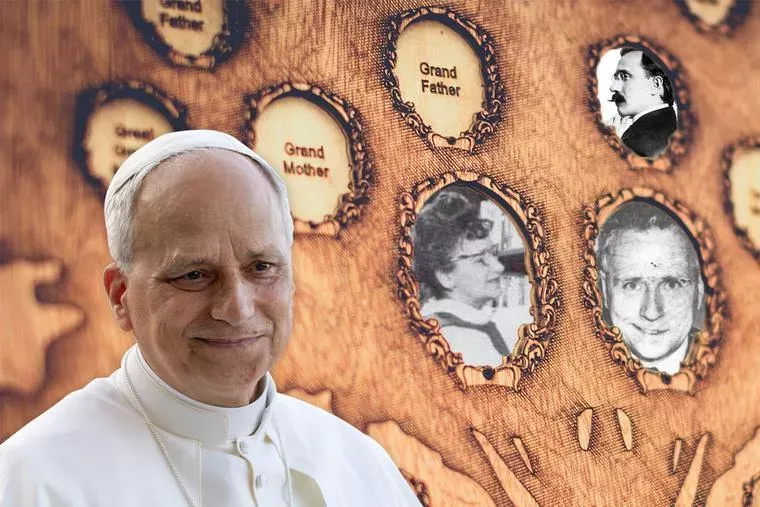

A Memorable Family Tree

Whatever the origins of their relationship, the Prevosts lived as Catholics. Giovanni/John had a Catholic funeral Mass when he died in 1960, as did Suzanne in 1979. Her death notice described her as a Third Order Carmelite, meaning she was a lay member of the religious order and voluntarily took on Carmelite spiritual practices.

The Prevosts raised their two boys as Catholics, and it stuck. The older boy was described as “a daily communicant” when he died in February 1996, according to a death notice. The younger boy became father of a pope.

The Register asked several Catholic clerics about the Pope’s unusual ancestry.

“Well, we’ve all got some nuts falling out of our family tree. It is interesting that his last name is Prevost and he carries it as a legacy of unchaste union,” said Msgr. Charles Pope, pastor of Holy Comforter-St. Cyprian Catholic Church in Washington, D.C., and author of The Hell There Is: An Exploration of an Often-Rejected Doctrine of the Church (March 2025), by email. “Nevertheless, God can make a way out of no way and write straight with the crooked lines of our lineage.”

As for the Pope’s grandparents’ situation, Archbishop Thomas noted that the genealogy of Jesus in Chapter 1 of the Gospel of Matthew has been a stumbling block for some, because, along with holy people and unknown people, it includes idolaters, murderers, prostitutes and adulterers.

“The life of Jesus is founded not on human greatness and achievement, but on forgiveness, mercy and hope. This is our inheritance,” Archbishop Thomas said.

“The genealogy of Jesus, rather than being a source of embarrassment, is a cause for rejoicing. It stands out as a beacon of hope, a light in darkness, and a proclamation that no one is beyond the reach of the cross,” he said. “This will be the enduring message of the pontificate of Pope Leo XIV."