I was invited to the abbey by Benedictine Father Fabrice Vovor, a priest — and school inspector — from the closest city, Kpalimé, where more than 40% of the people are Catholic. Nationwide, the percentage of Catholics is about 25% of the 6 million population, making Catholicism the largest Christian religion.

Growing up, Father Vovor enjoyed visiting the monastery, which helped clarify his vocation. He concluded he needed more engagement with the world, so opted to become a diocesan priest.

Father Vovor completed a compelling doctorate at Paul-Valéry University in Montpelier, France, that will be published next year: From Foreign Missionaries to an Indigenous Togolese Clergy: The Impact of Africanization on Evangelization and Society, 1892-1967. After studies in Italy, a bishop asked him to stay to work in a northern Italian parish, but, he recounted, “I didn’t want to stay in Italy, I wanted to do something for my people who need help.”

The priest returned to Togo where his first assignment was running St. Michel College, a middle and high school. It was dilapidated and had few resources, such as books or school supplies. So Father Vovor reached out to Italian friends; they contributed so generously that the school embedded an honorary plaque in a public-facing wall. (He substitutes regularly for priests in the Piedmont region while they vacation.)

Classroom at College St Michel.(Photo: Victor Gaetan )

Classroom at College St Michel.(Photo: Victor Gaetan )

(Story continues below)

We stopped at the school on our way to Lomé, the capital city. Children, ranging from ages 10 to 19, were thrilled to have guests. Although the chalkboards are old-fashioned, the children were happy and lively, dressed in crisp pink and tan uniforms. It’s a trip back in time, before the takeover of childhood by smartphones.

Schooling the Nation

Catholic schools and public schools in Togo have the same curriculum, although Catholic schools teach ethics more explicitly and have Mass at least once a month.

“It’s a major form of influence,” said Father Vovor. “Most political people received a Catholic education themselves, so they know our values and so do their children. It creates respect.”

As we travel down the main road to the capital city, it seems every five miles we encounter a Catholic school. We stop at a precious nursery school run by the Sisters of Notre Dame de L’Église, a domestic order created in 1952 by Lomé’s first archbishop, a French-born priest, Archbishop Joseph Strebler of the Society for African Missions.

Fr. Fabrice Vovor who serves as school inspector.(Photo: Victor Gaetan )

Fr. Fabrice Vovor who serves as school inspector.(Photo: Victor Gaetan )

Asked why she dedicates herself to the little ones, Sister Victoria summarized the attitude of so many religious men and women in this field: “I think with education we can help people have a future. To have a better life. To fight against poverty. There’s nothing more important here.”

Closer to the capital, in the Apessito neighborhood, we visit an impressive complex where the Canossian Daughters of Charity manage two ambitious schools: Institut Superieur Agata Carelli (ISAC), a private university, and Centre Catholique de Formation Technique et Professionelle, a trade school for young women.

Sr. Victoria with her students at the primary school in Togo. (Photo: Victor Gaetan )

Sr. Victoria with her students at the primary school in Togo. (Photo: Victor Gaetan )

Laughing and taking pictures of each other in front of school gates, Reine and Ida said they are busy learning fashion and hairstyling at their “great school!”

The principal, Sister Thérèse Djamongue, greets us outside, next to a sign with an icon and the wonderful message, “Jesus Christ is the true reason for this school. He is the invisible teacher, always present in classes. He is the model for all personnel and inspiration for all students.”

The Canossians began this mission in Togo 30 years ago. In 2015, the order added a medical facility, the Bakhita Health Center, named after the renowned Canossian, St. Josephine Bakhita, patron saint of slaves and victims of human trafficking.

Students who attend a school run by the Canossians.(Photo: Victor Gaetan )

Students who attend a school run by the Canossians.(Photo: Victor Gaetan )

Fruitful Vocations

Togo’s Catholic community suffered a major loss with the death last year of Lomé Archbishop Nicodème Barrigah-Benissan at age 61. He has not yet been replaced.

The prelate was renowned nationwide as a singer and playwright: he won the Grand Prize for Togolese Literature in 2020. He was also a moral authority who led the bishops’ conference’s Truth, Justice, and Reconciliation Commission investigating political violence in Togo between 1958-2005, a report presented to the nation’s president in 2012. For 11 years, Archbishop Barrigah even worked as a Vatican diplomat, serving in Rwanda, El Salvador, Cote D’Ivoire and Israel between 1997 and 2008.

Attending Mass at an impressive new church in Lomé, St. Rita Parish of Tokoin-Wuiti, I noted the archbishop’s influence reflected on the dedication stone, marked 2022.

Father Hermann Houdji is parochial vicar at St. Rita’s, ordained two years ago. He explained that the country’s bishops’ conference worked hard to strengthen priestly formation. In fact, so many young men were applying to seminary that the standards had to be made stricter. Togo now has three inter-diocesan seminaries, in three different parts of the country, educating priests at different stages of vocational education.

Fr. Fabrice and Father Hermann at St. Rita's Catholic Church. (Photo: Victor Gaetan )

Fr. Fabrice and Father Hermann at St. Rita's Catholic Church. (Photo: Victor Gaetan )

Statistics reflect a marked national increase in Catholic priests, both diocesan and religious, over the last 15 years to serve the country’s six dioceses and one archdiocese.

Father Vovor explains, “The Church is experiencing great vitality, even a renaissance, in nearly every place. Children, altar servers, choir members are encouraged throughout the early years to enter seminary, so they develop a desire to become priests.”

“This is a most splendid time for the Togolese Church,” the priest-educator said. “Even the most peripheral parts of the country are well served”— including the mountains where coffee is born.

Students attending Catholic nursery school pose for a photo in Togo. (photo: Victor Gaetan / National Catholic Register )

Students attending Catholic nursery school pose for a photo in Togo. (photo: Victor Gaetan / National Catholic Register )

Abby of the Assumption Benedictine Monastery in Togo. (Photo: Victor Gaetan )

Abby of the Assumption Benedictine Monastery in Togo. (Photo: Victor Gaetan ) Fr. François Amouzou poses next to a coffee plant. (Photo: Victor Gaetan )

Fr. François Amouzou poses next to a coffee plant. (Photo: Victor Gaetan )

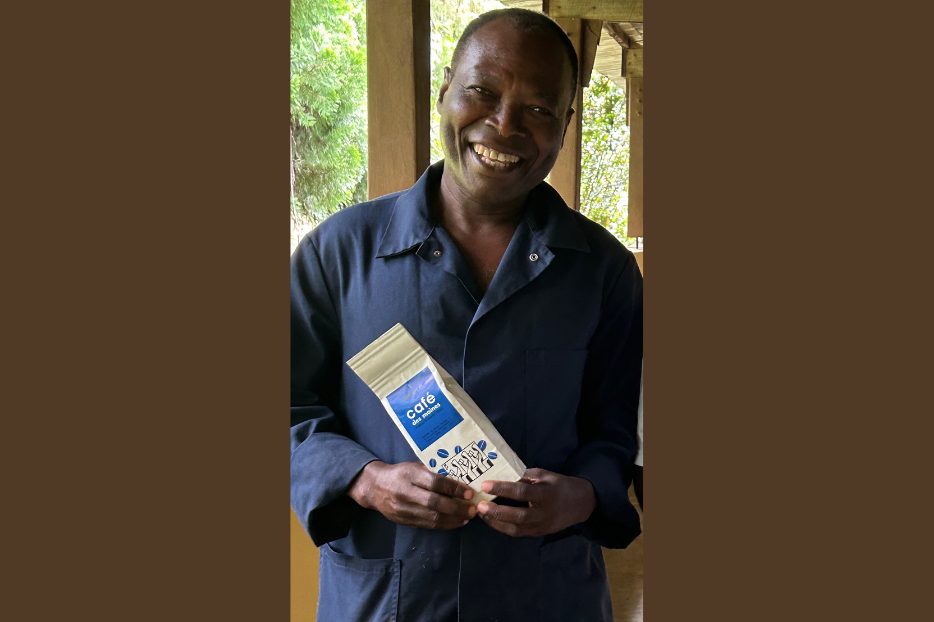

Fr. François Amouzou with coffee.(Photo: Victor Gaetan )

Fr. François Amouzou with coffee.(Photo: Victor Gaetan ) Classroom at College St Michel.(Photo: Victor Gaetan )

Classroom at College St Michel.(Photo: Victor Gaetan ) Fr. Fabrice Vovor who serves as school inspector.(Photo: Victor Gaetan )

Fr. Fabrice Vovor who serves as school inspector.(Photo: Victor Gaetan ) Sr. Victoria with her students at the primary school in Togo. (Photo: Victor Gaetan )

Sr. Victoria with her students at the primary school in Togo. (Photo: Victor Gaetan ) Students who attend a school run by the Canossians.(Photo: Victor Gaetan )

Students who attend a school run by the Canossians.(Photo: Victor Gaetan ) Fr. Fabrice and Father Hermann at St. Rita's Catholic Church. (Photo: Victor Gaetan )

Fr. Fabrice and Father Hermann at St. Rita's Catholic Church. (Photo: Victor Gaetan )