Athanasius notes, for example, the Gospel of St. John states that “in the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God.” He also cites Chapter 8 of the same Gospel in which Christ declares “before Abraham was, I am,” invoking the divine name used by God to indicate his eternity when appearing to Moses as the burning bush.

“The Lord himself says, ‘I am the Truth,’ not ‘I became the Truth,’ but always, ‘I am — I am the Shepherd — I am the Light‘ — and again, ‘Call me not, Lord and Master? And you call me well, for so I am,‘” Athanasius wrote. “Who, hearing such language from God, and the Wisdom, and Word of the Father, speaking of himself, will any longer hesitate about the truth, and not immediately believe that in the phrase ‘I am,‘ is signified that the Son is eternal and without beginning?”

Legge noted that Athanasius also warned that Arius’ position “threatened the central truth of Christianity that God became man for our salvation.”

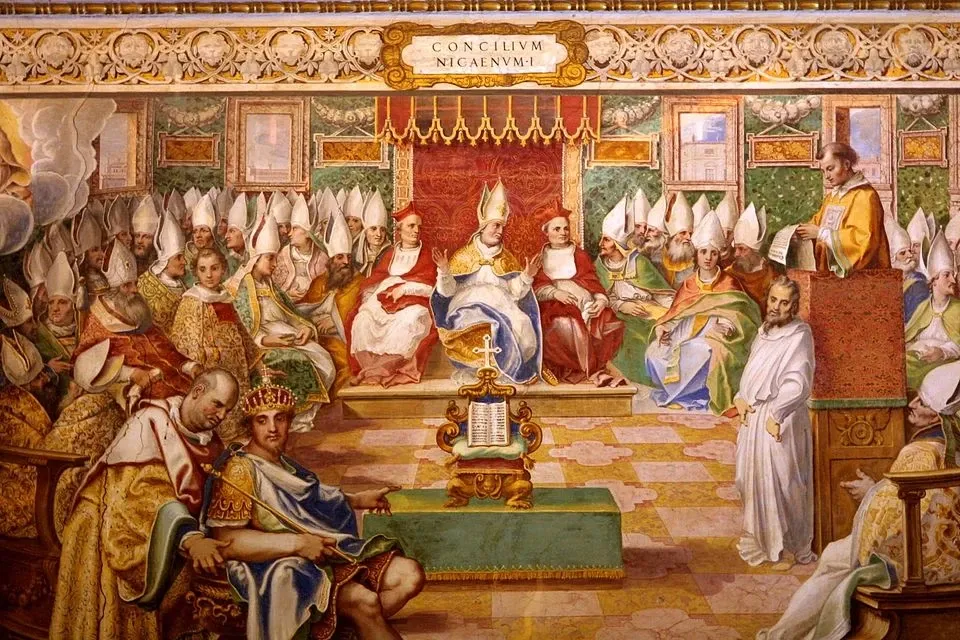

Unifying the Church in the fourth century

Prior to the Council of Nicaea, bishops in the Church held many synods and councils to settle disputes that arose within Christianity.

(Story continues below)

This includes the Council of Jerusalem, which was an apostolic council detailed in Acts 15, and many local councils that did not represent the entire Church. Regional councils “have a kind of binding authority — but they’re not global,” according to Thomas Clemmons, a professor of Church history at The Catholic University of America.

When the Roman Empire halted its Christian persecution and Emperor Constantine converted to the faith, this allowed “the opportunity to have a more broad, ecumenical council,” Clemmons told CNA. Constantine embraced Christianity more than a decade before the council, though he was not actually baptized until moments before his death in A.D. 337.

Constantine saw a need for “a certain sense of unity,” he said, at a time with theological disputes, debates about the date of Easter, conflicts about episcopal jurisdictions, and canon law questions.

“His role was to unify and to have [those] other issues worked out,” Clemmons said.

The pursuit of unity helped produce the Nicene Creed, which Clemmons said “helps to clarify what more familiar scriptural language doesn’t.”

Neither the council nor the creed was universally adopted immediately. Clemmons noted that it was more quickly adopted in the East but took longer in the West. There were several attempts to overturn the council, but Clemmons said “it’s later tradition that will affirm it.”

“I don’t know if the significance of it was understood [at the time],” he said.

The dispute between Arians and defenders of Nicaea were tense for the next half century, with some emperors backing the creed and others backing Arianism. Ultimately, Clemmons said, the creed “convinces people over many decades but without the imperial enforcement you would expect.”

It was not until 380 when Emperor Theodosius declared that Nicene Christianity was the official religion of the Roman Empire. One year later, at the First Council of Constantinople, the Church reaffirmed the Council of Nicaea and updated the Nicene Creed by adding text about the Holy Spirit and the Church.

Common misconceptions

There are some prominent misconceptions about the Council of Nicaea that are prevalent in modern society.

Clemmons said the assertion that the Council of Nicaea established the biblical canon “is probably the most obvious” misconception. This subject was not debated at Nicaea and the council did not promulgate any teachings on this matter.

Another misconception, he noted, is the notion that the council established the Church and the papacy. Episcopal offices, including that of the pope (the bishop of Rome), were already in place and operating long before Nicaea, although the council did resolve some jurisdictional disputes.

Other misconceptions, according to Clemmons, is an asserted “novelty” of the process and the teachings. He noted that bishops often gathered in local councils and that the teachings defined at Nicaea were simply “the confirmation of the faith of the early Church.”

This article was first published on June 5, 2025, and has been updated.